The main topic of our conversation with the horse is BALANCE. Together the horse and I have to work out a language through which we can understand each other. I think that the process is very much trial and error or should I say trial, error, learning, trial…

To begin with we communicate to build mutual understanding and balance. We can then ask questions to test understanding and ability to maintain balance.

Have you ever tried to learn a new language? I am going through the process of learning French right now. I think that all riders should attempt to learn another human language themselves. That way they can understand better the process the horse is going through. I learn better with repetition; in context (ie it is useful); when I am closer (face to face is best); when it is “real” and there is a reason; when I feel I can have a go and be corrected without ridicule.

Because I don’t think in French I have to stop and think how to say what I want to say in French. Sometimes I can’t because I don’t have the words. Then I have to think of other ways of saying the same thing. It is amazing. Often there are hundreds of slightly different ways of saying the same thing. This means that I must choose. Because I don’t have to do this in English I don’t really make a conscious choice. Sometimes I think it would be better to do this in English too… there is always another way.

The point I am trying to make is that it is good to think about communication before you do it. What impact are you trying to make? How could that be achieved? What is the best way to achieve it? It works for people. It works for horses. Don’t give away the power to choose.

Stephen Covey (2), a renowned management consultant, states in his book, “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People”, that to do this we must first seek to understand then seek to be understood. But first of all, before seeking to understand others, I think we need to really understand ourselves…

Before we start a conversation or ask any question of our horse we must first ensure we are prepared by “questioning” ourselves. The full time job of the rider is balancing herself. Only by balancing herself can she minimise the burden to her horse. This involves becoming highly body aware.

The rider constantly assesses her balance and rebalances herself. Ensuring she is straight (even weight 50/50 Left to Right) and using only the minimum amount of tension in the muscles and releasing any excess tension. It is only possible to do this when our body comes into natural alignment. Then and only then can we “let go” and release our insides to where they would naturally like to be. This carriage and freedom allows the horse’s energy to pass “through” us without any blocks. How can he move loose and free when we are stiff and blocking? The rider takes her attention inside herself; identifying areas of tension and releasing (literally thinking it free). Learning how to do this is the focus of the Alexander Technique (see chapter 8).

The rider does this before every change of direction, every transition and many times per minute. The external observer is unable to see this. The activity is internal and flowing. There is a lot going on but it is happening on the inside not the outside.

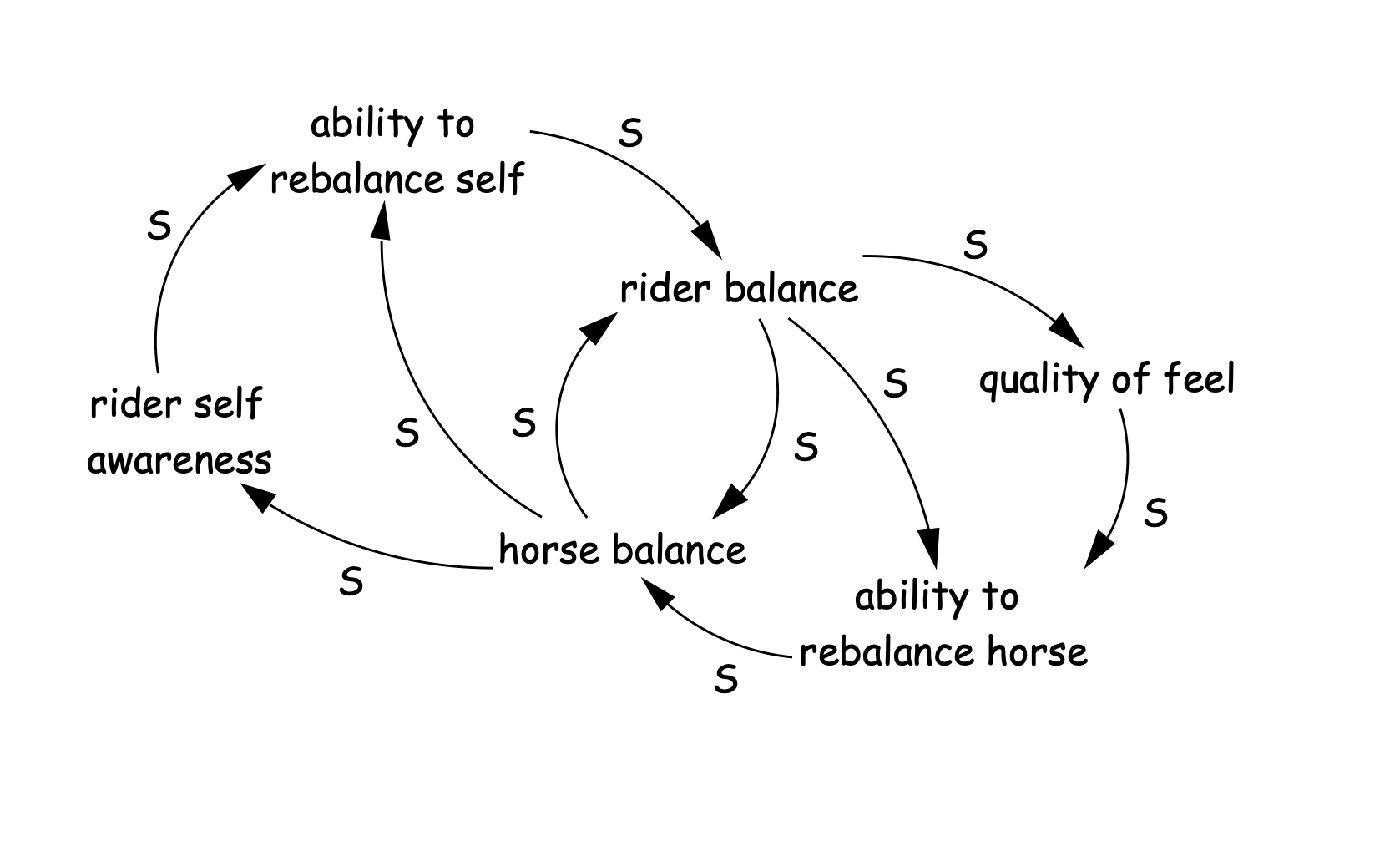

So, the rider feels and rebalances herself. Then she feels the horse and rebalances him using movements. On and on and on………

No riding instructor taught me this. I learnt it myself from Alexander lessons and then experimented with it on the horse. The single thing that I do all the time when I’m riding and lunging well is something no-one told me!

Figure 23 Balancing Loop "Balance"

I think that Sally Swift is referring to this in her “Centred Riding 2” (12) when she talks about “dropping a ball” down through herself.

The rider half halts herself. And this half halts the horse. This doesn’t involve the use of hands or legs. It is far more subtle.

Degrees of balance

A person is balanced in body when there is equal weight left and right. It is the same for our horse. Our balance is challenged when we try to do more difficult activities. For example, my balance could be fine to sit in a chair but can I walk a tightrope? Our horse is fine grazing in the field but what about galloping flat out down a muddy slope? Horse and rider can individually be balanced when static but movement will challenge that balance.

As a rider we need to constantly assess, reassess and re-balance – ie adjust weight distribution. To assess we need to find a “place” where we can feel – not just in our hand but in our whole body – a quiet place where we are literally doing nothing, where we become aware of our balance.

Many riders, myself included, suffer from an inability to “assess what is happening now”, because we are too busy doing too much with our bodies and wanting to be somewhere else in our minds (by now I should be doing x,y,z with my horse). In this we miss out on understanding what we have NOW!

The horse can’t find his balance if we are constantly changing things, niggling and interfering. The horse uses his head and neck to balance himself so you must interfere as little as possible with the horse’s ability to do that. Cultivate a giving forwards hand that never blocks, not even momentarily. Trust that the horse will come into a beautiful carriage when he can. This may be after 5 minutes or 5 years! But it will come.

If you try to fake it by artificially positioning the horse’s head with special equipment what will happen when you take away the support of this artificial aid? What do you want – look or feel? When it feels right it will look right – but it doesn’t necessarily work the other way around. Think of riding the horse’s ears forward away from you – think that you can make his neck longer. Never think of shortening his neck or “pulling him together” or fiddling his head down.

The horse can’t “forgive” our bad riding because it affects his balance. But he will never bear malice and hold it against you in the next session! However, he does have a long memory and bad experiences are not easily forgotten. The horse lives in the moment and reacts to what is happening now. He doesn’t think “oh last time she rode me she completely restricted my canter because of her seat so this time I’ll show her and make it uncomfortable for her”. He seems to know when we are trying to improve and is eternally patient with us. He is less patient when we are intentionally seeking to manipulate him.

Horses tend to do what we enable them to do. Unfortunately this is not always what we want! This means that we have to learn how to ask properly and not get in the way (and so make it as easy as possible for the horse to comply).

The true test of balance is when the horse carries himself and the rider, unaided, without support from the hand. This can be proven by giving away one or both reins or by riding with a loop in the reins with no change in the beautiful outline. It can also be tested by the horse seeking the rein forwards and down in walk on a long rein or similarly with trot and canter. I think that these movements should be given at least twice the marks in all dressage tests.

What factors affect balance?

Here are some ideas to get you started:

-Horse conformation, fitness and strength

-The shape of the rider and the horse

-Rider’s “talent”

-Rider conformation and fitness

-Rider’s ability to manage posture – body control

-Rider’s ability to release tension – body awareness

-Base of support - connection to the ground

-Engagement of horse’s hind legs

-Consistency of surface

-Confidence that you won’t fall

-Gradient

-Balance challenge in movements

-Consistency – an uneven load can be accommodated as long as it is consistently uneven.

What are the signs that you and/or your horse have lost balance?

This can manifest in a number of ways: lack of straightness, falling in/out on circles, rhythm changes, tempo changes, horse comes against hand/leans on hand, trips/falls over/stumbles.

What causes loss of balance?

The responsibility could be with the horse or the rider or a little of both. It doesn’t really matter who is “to blame”. What matters is recognising and correcting without overcorrecting. We have to pay attention to and manage balance every moment that we ride.

For example, in canter, if the rider tenses because she loses physical balance or tenses because she loses mental balance (eg oh no here comes that sticky corner again) she will unbalance the horse. In addition, the horse may himself become unbalanced. This may happen quickly through a change in the quality of the surface or a sudden change of direction. He may become unbalanced gradually, in canter becoming longer and longer and more and more on the forehand. Inevitably he will fall out of canter into a long and disorganised trot.

How do we recover balance?

The answer depends on the cause and how great the loss of balance actually is. Prevention is always better than cure. Usually prevention is through preparation.

Useful rebalancing exercises include –

-Reducing speed (slowing the rhythm) – using the body, or if absolutely necessary, with the hand, but then giving to allow the horse to re-find his balance

-Controlling the tempo with a controlling seat

-The half halt

-Reducing the pace – it is easier for the horse to balance himself in walk than trot, in halt than walk and so on

-Using the circle (remember a circle gives the opportunity for “no change”)

-Using the school walls

-Using poles

-Not overdoing things - only do as much as balance can be maintained then reduce pace and start again. For example, it is better to have 6 good canter strides then transition to trot and repeat. In this way the rider gradually builds confidence by being able to reward him rather than waiting for him to fail! An excellent example of using this to teach the horse to counter canter is given in Michel Henriquet’s book (10). He advocates riding a diagonal and then letting the horse make as many strides as possible and gradually building this up. The rider’s task is to be a neutral force and allow the horse to work out how to keep his balance for himself.

Self carriage is a very interesting term, as it means more than balance to me. Carrying the self, taking responsibility for our own weight, is not just about our body-weight. The self is also the mind, so we must also take responsibility for the “weight of our mind”, make good choices – fairly, and take responsibility for the outcomes. Yes, self carriage is as important in life as in riding……….

Attention – active listening

On a recent visit to the UK I met up with a horsey friend who I hadn’t seen for some time. My non-horsey partner was with me at the time. My friend and I talked and talked and talked – you know how it is – I completely forgot about time and other visits we had promised to make to other folk.

Afterwards my partner told me that he had been getting more and more frustrated with me. He told me I had been ignoring his signs to leave on purpose. I told him that I hadn’t even noticed him making any signs. That was the truth!

What should my partner have done?

What does it teach us about interacting with our horse?

I think the moral of the story is that to communicate we need attention. To receive this attention we must be more compelling than the distractions. With the highest levels of attention and trust we have the ability to stay focussed despite the chaos around us. This is probably best witnessed in the dressage competition world…those with attention and trust are better able to perform in the most trying circumstances.

We can keep attention by frequent change of direction, of pace, of exercise. We must strike a balance between change to maintain attention and avoid boredom and repetition to reinforce learning.

~

[…] as „Thermostat-Theory“ (Friedrich/Sens1976), it is equated with Norbert Wieners technical control circuit cybernetic model (1948), as cybernetics describes steering and control processes in „machines as well as in life-forms“ (Wiener 1948, 32; also Friedrich/Sens 1976, 39; Geyer 1995, 7-12; Robb 1984, 21). And as a matter of fact, the 1940s’ and 50s’ paradigm was the thermostat, as a model of controllable feedback. Balance and system maintenance were seen as the research-guiding backdrop for the correction of external disruptions, […]

DEGELE, Nina, 2008. On controlling complex systems—a socio-cybernetic reflexion. Journal of Sociocybernetics. 2008. Vol. 6, no. 2, p. 55–68, p. 58.