…In order to complete Urban Regeneration with Design-Build Adaptation, a smooth process of entitlement is needed.

__Problem-statement: Too often the entitlement process for urban development is irrational, contradictory, confusing, uncertain — and too expensive.__

Discussion: The contribution of the entitlement process — planning applications, design review, building permits, inspections and so on — to the increasing cost of development has been widely discussed. This regulatory framework is widely acknowledged to be essential to protect public health and welfare, by requiring better-quality development, and by frequently allowing public and judicial review of the design quality of projects.

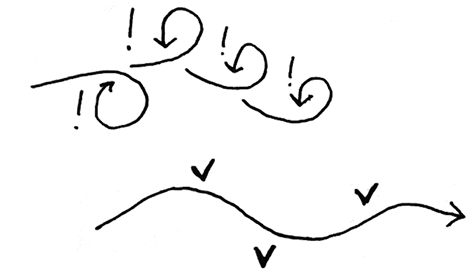

Paradoxically, however, sometimes the result is lower quality, as builders and developers seek to cut corners and “game the system.” Moreover, the uncertainty and delay introduced in to the process increases risk, which translates into increased cost — moving in exactly the wrong direction when it comes to the need for more affordable homes.

In response, some advocates of affordable housing have suggested that the answer is to force projects through over the objections of local residents. But residents have a stake in the quality of their public realm, and in how adjacent private development impacts their quality of life. In most cities, they are granted the right to participate in the “co-production” of their neighborhood and its public realm (see CO-PRODUCTION, 12.2). Moreover, a constructive, “win-win” approach between residents and developers can actually result in better projects — more popular with neighbors, buyers and renters, and more financially successful for the owners.

This leaves the problem of the jurisdictions, whose bureaucratic processes are often a bigger problem. One of the most common problems is regulatory mis-alignment, meaning that procedures in one department or jurisdiction are in conflict with those in another.

A more “agile” strategy would be to find already successful types and patterns that meet the regulatory standards, and are considered compatible and even desirable by the stakeholders. In process, the jurisdictions and stakeholders (including potential developers) would collaborate to identify essentially pre-entitled elements, models, types, and even entire plans (say, for a particularly popular kind of residence or shop building). These pre-entitled structures could still be customized with unique elements — see Economies Of Place And Differentiation — but their essential patterns could be pre-accepted (even as part of a local pattern language just for that neighborhood).

In this way, the problem of residents objecting, and being stigmatized as NIMBYs — whose default position is “Not In My Back Yard” — can give way to residents who support QUIMBY — “Quality In My Back Yard.” They would then be contributing to the positive growth of the neighborhood, instead of being able only to resist (perhaps in vain) its degradation.

__Therefore: Set up a process of entitlement streamlining, involving the stakeholders of each neighborhood and the members of the various bureaus who can help to simplify and streamline the process. After prototype design elements and plans are identified, work to review and pre-approve them, so that applicants can greatly reduce time — in some cases pulling permits over the counter.__

Use entitlement streamlining as part of the Neighborhood Planning Center and its work. Visualize the structures that are candidates for pre-entitlement with Community Mockup and Augmented Reality Design tools. …

notes

¹ See Pamela Blais’ description of the “perverse” outcomes of these regulatory systems, in Blais, P. (2011). Perverse Cities: Hidden subsidies, wonky policy, and urban sprawl. Vancouver: UBC Press.

See more Implementation Tool Patterns