The problem with the term extended cognition centers on the fact that it misses the ghost in the box quality or phenomenon Luhmann, and other scholars have described.

However, there may be some validity to the issue Yeo points out concerning the term extended. For this reason, Scott P. Scheper chooses to retain the term Mind (in order to encapsulate the ghost-like spirit and the experience of having internal dialogue).

> However, I opt to drop extended, and prefer second in its place.

Why? Because as Yeo points out, extended is a rather vague term. Is it truly extended thought since it’s really my own thought? Or is it rather a second storage mechanism for my own thought? As a result, I opt for second. -- Scheper, Antinet Zettelkasten.

The reason handwritten notes produce the ghost in the box effect (that is, preserving your past self [⇒ preserve]) seems to emanate from one thing: Consciousness. Handwritten notes capture your own experience, sentiments, and sentience at the time you wrote your thoughts on the card.

This entire experience enables me to connect with the reader more and communicate the idea properly by sharing with the reader my own initial skepticisms when presented with an idea. For instance, I know what you’re about to read may sound suspect. I realize the concept of ‘communicating with a ghost in a box of notecards’ sounds like woo-woo Mysticism [⇒ Holographic New Age Mysticism]. Yet, this is precisely how the greatest social scientist of the 20th century explained the Antinet.

The inner life of the Antinet is brought about by two things. First, it revolves around creating a communication partner (a second mind, a ghost in the box, and an alter-ego).

The numeric-alpha addresses [⇒ Domain Name System] enable the Antinet to refer to itself and its own individual parts. It’s a key piece for creating the personality (the ghost, the alter ego). As a result, observes Cevolini, “Interaction” with the Antinet, becomes “a type of communication”—an internal dialogue. (Alberto Cevolini, ed., Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe, Library of the Written Word, volume 53 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016), 28.)

Ghost writers are behind more books than you’ll ever know.

~

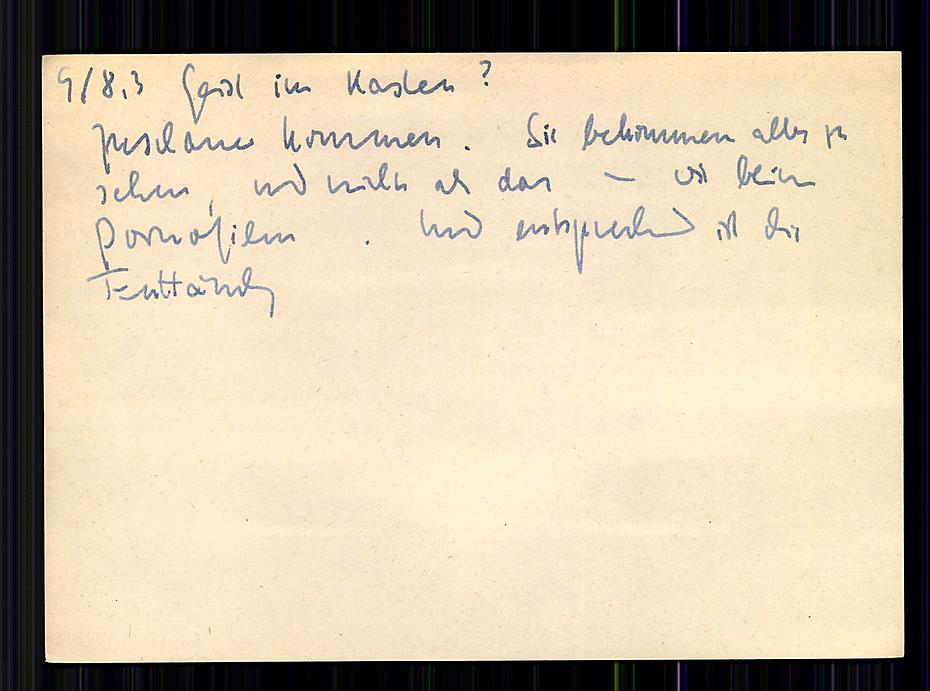

Zuschauer kommen. Sie bekommen alles zu sehen, und nichts als das – wie beim Pornofilm. Und entsprechend ist die Enttäuschung.

~

> Spectators come. They get to see everything, and nothing but that - just like in a porn Movie. And the disappointment is accordingly.

You would have to do a lot of digging to discover how Luhmann actually viewed his Zettelkasten: as a second mind, a ghost in the box, or an alter ego with whom he communicated.

This type of stuff may sound sappy and unscientific; however, I assure you it’s not. The Antinet contains your personality, and this is a very important feature in interacting with your own thoughts. As previously mentioned, scholars, including Luhmann, are aware of the idea of a ghost in the box. One scholar concludes that “Luhmann did not regard his filing cabinet as a simple slip box, rather he interacted with it as if it were a true communication partner.” (Alberto Cevolini, ed., Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe, Library of the Written Word, volume 53 (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2016), 26. Emphasis added.)

The ghost in the box factor stems from writing by hand. Handwriting seems to containerize consciousness better than standardized digital fonts. Developing true knowledge, filled with meaningful information, relies on internal dialogue (i.e., intrapersonal communication) with your past self ’s consciousness. Analog systems with handwriting seem to retain this consciousness better than standardized digital schemes. Your own handwriting is unique—especially when you view it yourself.

Modern day scientists agree with Luhmann’s notion of a ghost in the box emerging from Antinets. One scholar confirms that it would be misleading to classify the Antinet as something which simply stores notes. Here’s why: when you peruse and read the thoughts written by someone who has passed—you feel this ghost-like internal presence. You begin to insert yourself in their shoes while they were writing down the thoughts on the card.

With the Antinet, this ghost in the box factor is experienced in a slightly different manner. You yourself are viewing your own thoughts. You communicate with your own internal ghost and embark upon an internal dialogue that happens during the act of creation.

[…] the concept of an internal ghost, internal monologue, and internal dialogue. Niklas Luhmann referenced this concept as well. The idea of the internal ghost has been observed and studied by scholars as the interaction between (1) external memory systems like the Antinet and (2) internal memory (which is the so-called wetware memory that resides inside your skull).

The reason Luhmann created his Zettelkasten in the first place is two-fold. First, Luhmann set out to create a system for retrieving things forgotten by memory. Yet after a certain point, as early as 1981, he discovered its true power—his Zettelkasten became a thinking tool and communication partner that emerged almost as if it were its own mind, a ghost in the box. More on this will be covered later. More pertinent right now, however, is the second reason Luhmann started his Antinet.

If you wish to take Luhmann seriously, then you must accept his notion that an alter ego arises out of an analog Zettelkasten. A ghost in the box arises in the form of a second mind (if you structure your analog Zettelkasten properly). This creates an entity that allows you to communicate with it in the first place.

Again, the importance of numeric-alpha addresses cannot be emphasized enough. It not only enables linking, it enables the self-referential composition of the Zettelkasten which gives it a unique personality. Luhmann holds this as one of the most important aspects of the system. The unique personality stands as the raw material which will help the Zettelkasten morph into an unexpected structure allowing you to communicate with the second mind, the doppelgänger, the ghost (or spirit, or mind) in the box, as Luhmann referred to it. This is the entity Luhmann was suggesting would communicate when he titled his paper, “Communication with Noteboxes.” Numeric-alpha addresses make this possible.

~

SCHEPER, Scott P., 2022. Antinet Zettelkasten. San Diego, CA: Greenlamp. ISBN 979-8-9868626-0-6. pdf ![]() , p. 151 (book)/ p. 153 (pdf)

, p. 151 (book)/ p. 153 (pdf)