How to set up a guided tour

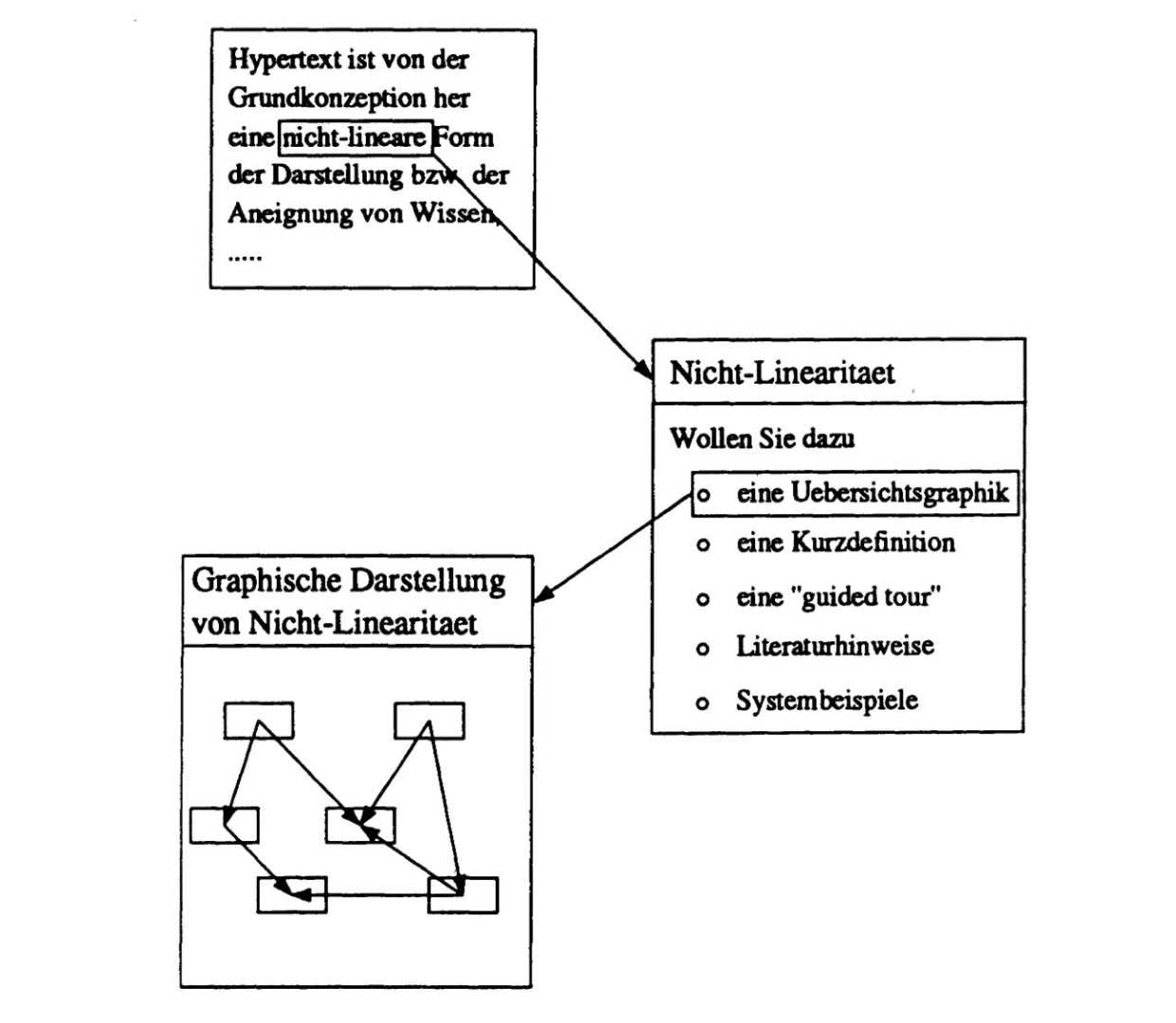

The places marked "_" in the rest of this section could be useful candidates for leaving the linear path in a hypertext: The reader could explore the nearer context in detail via a "fish-eye" perspective and absorb the more distant information only vaguely, or he could "zoom" as far as he wants and as deep as the system allows him, into all the material of the hypertext that is related to "non-linearity", or entrust himself to a path predefined by the author, thus goes on a "guided tour", which leads him from unit to unit in a controlled way, so that he can acquire knowledge about "non-linearity" in a systematic way, or he can "browse" and navigate in the whole material at his own will and ability, hopefully without what one almost existentialistically calls "lost in hyper space" happening.

This paragraph is a deliberate counterexample to the attempt otherwise made in this book to avoid the jargon of the Anglicisms that have also become common in hypertext, although some English expressions, e.g. "link", "web views" or "button", are more manageable than the German equivalents, "Verknüpfung", "verknüpfte Sichten", "Verknüpfungsanzeiger". Nevertheless, in only a few cases the original English terms were kept, e.g. "guided tour", but sometimes they were added in brackets after the German terms.

Fig.1.1-2. More complex possibilities of the expression "non-linearity".

[…]

See also Marshall/Irish (1989) with regard to "tabletops" (headings in "guided tours"); cf. section 2.3.

[…]

We discuss in more detail in Ch. 4 the possibility of generating flexible "abstracts" from text knowledge structures, i.e., abstracts that are not retrieved prefabricated, but are generated at reading time (in "read time") tailored to the user. Another interesting hypertext application for automatic summaries is to give users an overview of the content of the nodes to be visited in the path, not only in a graphical network, but also in textual form (cf. Section 2.3.4 on paths, web views, guided tours, etc.).

[…]

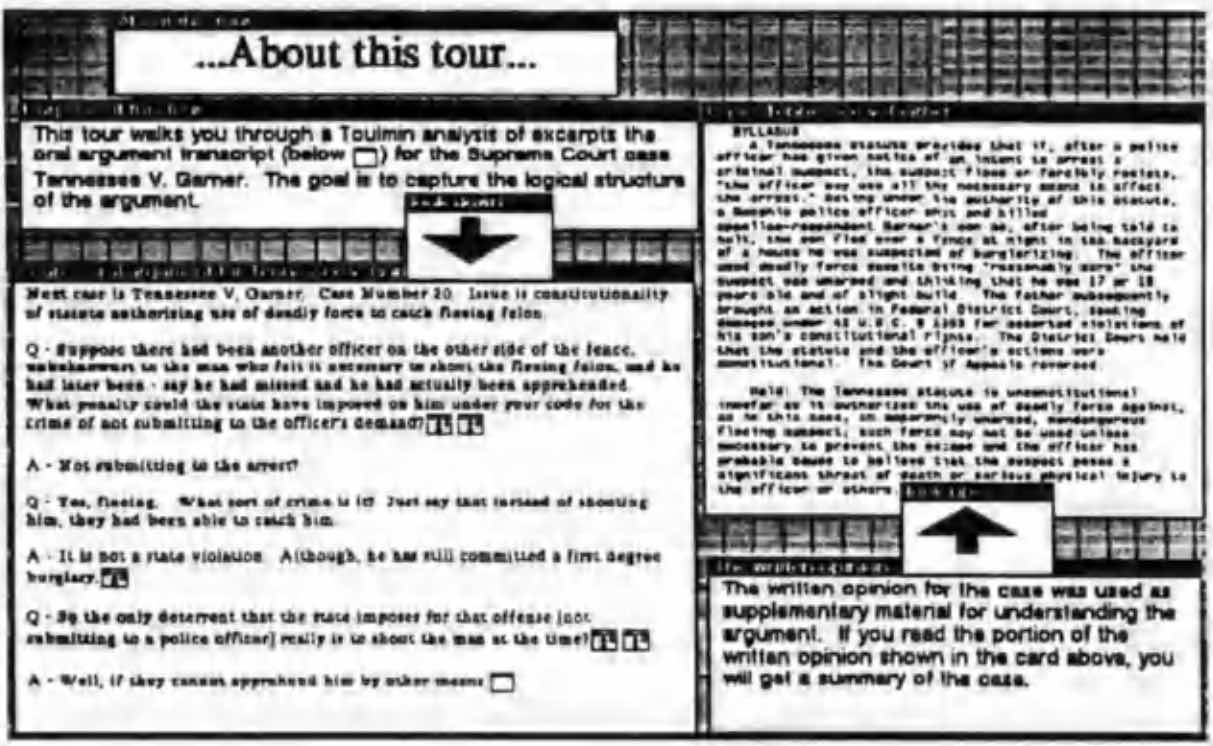

Fig.2.1.2-7. Information and meta-information in NoteCards (from: Marshall/Irish 1989, 18, Fig. 2; with permission of the ACM).

Metainformation, i.e., information that guides the user how to deal with the informational units and the linking offers, does not have to be placed in separate nodes, but can also be part of the informational units above, usually at the beginning or at the end of such a unit (that is why we have listed them as components of informational units in Fig. 2.1.2-6), but they can also be managed via the system's general orientation aids. Fig. 2.1.2-7 is part of a so-called "guided tour", as it is used with NoteCards. This possibility is discussed in detail in section 2.3.4. The different maps in Fig. 2.1.2-7 will be more understandable if, in advance, the explanations of Fig. 2.3.4-8 are read.

[…]

We show the "browsing" and "serendipity" effects that are typical for hypertext and that are desirable for creative information behavior, but also the orientation problems that arise in the process and see a corresponding need for orientation and navigation aids. Using the example of tables of contents and indexes, we demonstrate a) the application of more traditional non-linear navigation tools to hypertext and b) the development of hypertext-specific orientation and navigation methods, e.g., graphical overviews, paths, web views, guided tours, or dialog histories.

[…]

Marshall/Irish (1989) also rightly discuss Paths, or "guided tours" there, using NoteCards as an example, from the point of view of reconstructing coherence, context, and reference.

Guided tours, on-line presentations

Of the many pathways offered by hypertext systems, the concept of controlled guided instruction has become particularly influential. The term "guided tour" has come into use, following the terminology used in NoteCards. […] "Guided tours" are mainly useful for supporting unattended users, preferably in learning environments, but also generally for orientation in complex hypertext bases. Also with "guided tours" the users of the system, as with all paths, are led through relevant, coherent parts of the hypertext base. According to Zellweger (1989), the special art of building guided tours is to write instructions (in the case of NoteCards in the form of scripts) that do not define deterministic paths, as in techniques of programmed instruction, but ones in which the sequences of links remain non-linear. Furthermore, it should be possible to leave the guided tours at any point. In the following, we will take a closer look at the concept of the "guided tour" realized in NoteCards as presented by Marshall/Irish (1989).

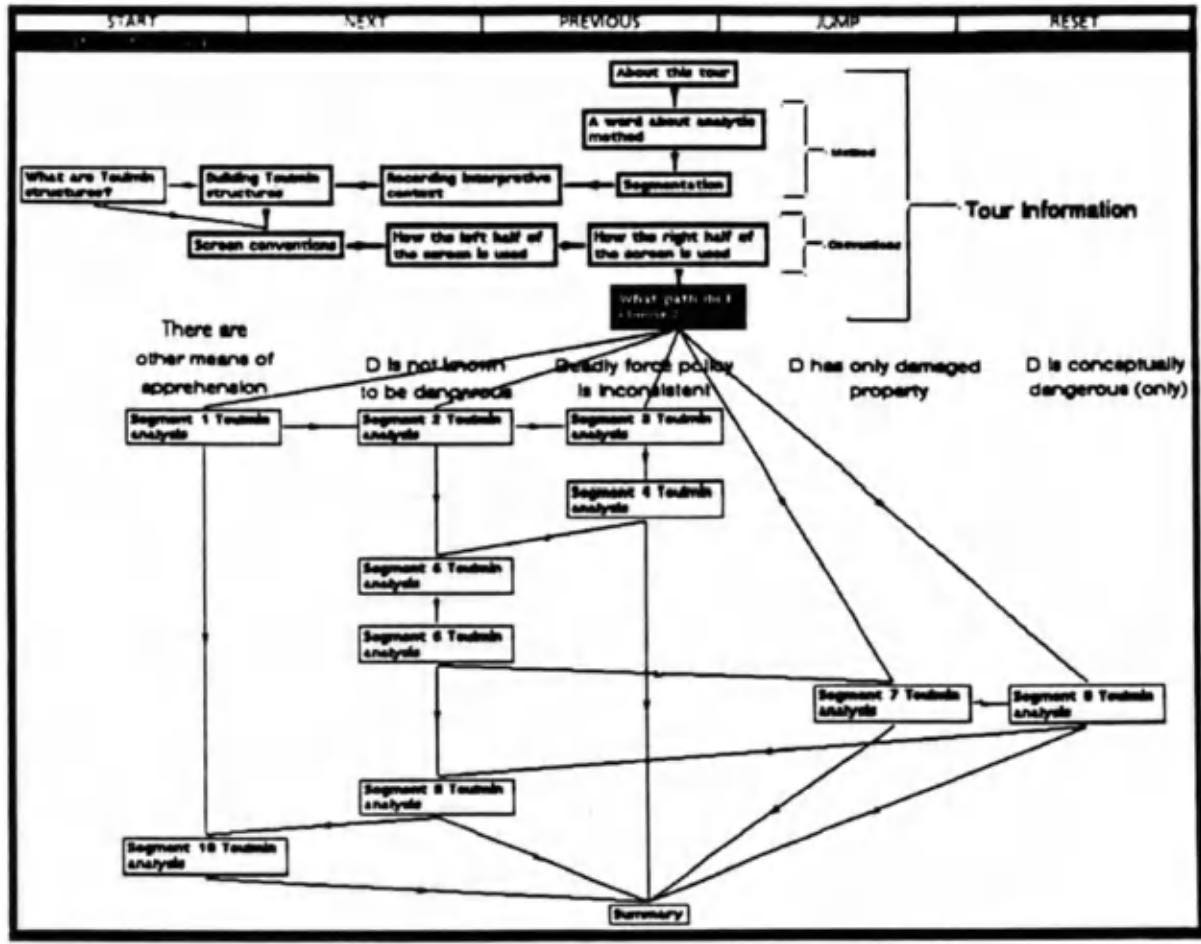

Fig. 2.3.4-7. Example of a "guided-tour" (from: Marshall/Irish 1989, 17, Fig. 1; with permission of the ACM).

Marshall/Irish (1989) point out that "guided tours" are especially suited to facilitate communication between authors and (future) readers. By appropriate means, the relevant (sub)structures of a NoteCards network can be displayed for author and reader. Figure 2.3.4-7 shows the general structure of a "guided tour".

The author builds the "guided tour" as a Graph in which special stops can be inserted at significant points. A special editor is available for this purpose. The stops are marked by the author with headings (so-called "tabletops"). These should be linguistically and graphically attractive and informative, but brief (largely in the style of a chapter heading or title).

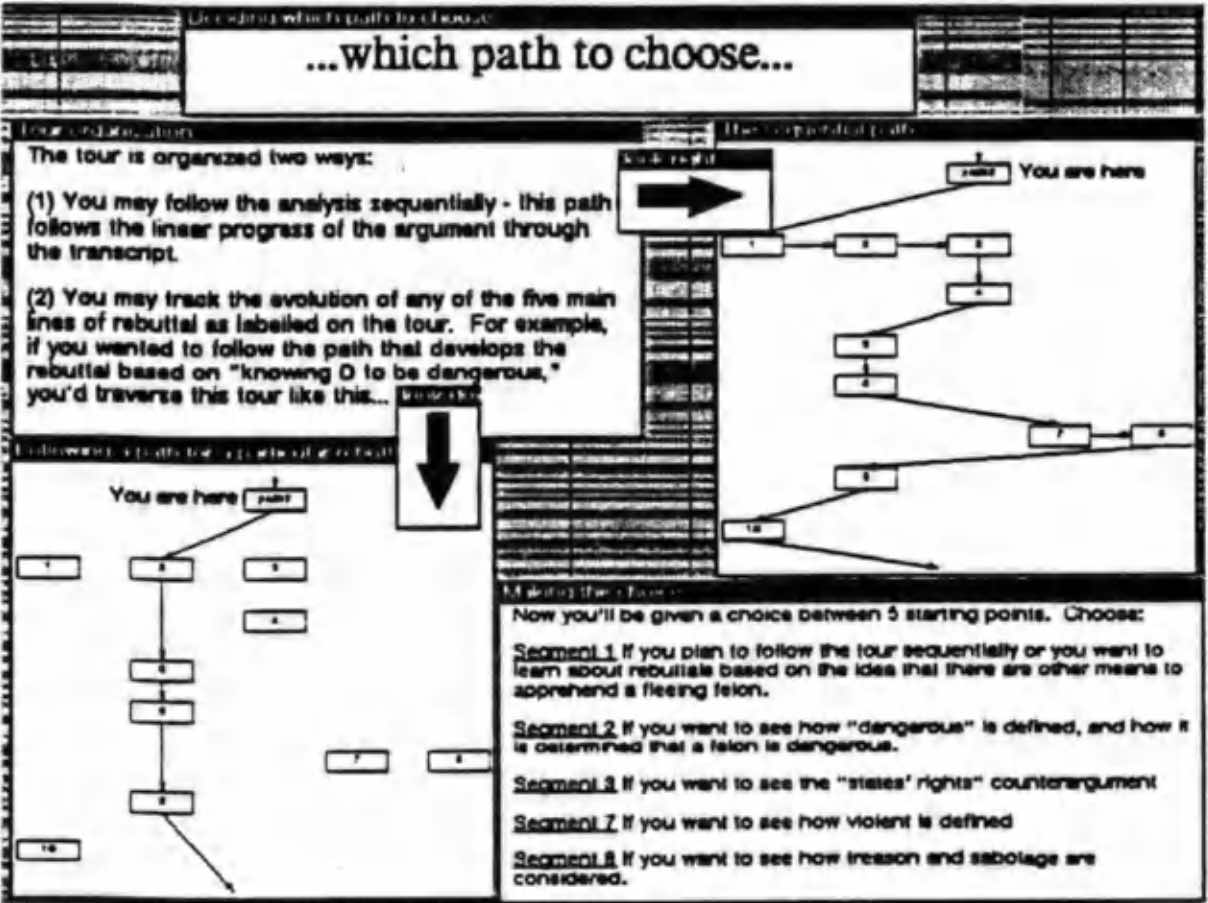

Fig.2.3.4-8. introductory caption of a "guided tour" ("tabletop") (from: Marshall/Irish 1989,21, Fig. 4; with permission of the ACM)

An example of a heading for the initial breakpoint "Introduction" is shown in Figure 2.3.4-8 (in the upper map: "which path to choose"). In this starting point of the tour, the different possibilities to enter the tour or to get an overview are presented in an introductory way, e.g. the indication in the upper left card how the tour is organized in general: sequential – then in the upper right card the way of working is shown graphically as a path – or selective (according to the graphical display in the lower left). And finally, the initial decision alternatives are compiled in the lower right corner. Other headings are included in the upper maps of Figures 2.3.4-9 and 10. They are typographically designed in the same way and are placed in the same position.

"Guided tours" are never "reeled off" and are also never self-explanatory from their informative parts, but contain, as we have already seen in Figure 2.3.4-8, a variety of meta-information, which thus serve to make the structure and the choices clear to the reader. However, the advantage of this orientation may have to be bought at the price of system dominance (danger of overload). Metainformation corresponds in some respects to the cohesive functions mentioned in sections 1.1 and 1.3; it establishes syntactic and semantic coherence between map units, which tend to be atomized. In syntactic terms, sequences are regulated or suggested; in semantic-argumentative terms, the individual units are placed in larger contexts of meaning. The meta-information in "guided tours" is an example of how context and coherence can be reconstructed in contextless environments. The possibilities offered are e.g. (graphical or tabular) tour overviews, reading instructions "look down", "look up") or short indicative overviews of what the next stop can bring. In NoteCards, arrow metaphors are mainly used to achieve referencing between different map types, e.g. between text and graphics, between meta-information and (actual) information, or between the same map types (also from meta-information to meta-information). Examples for the use of arrows can be found in Figure 2.3.4-9 and 10.

NoteCards also otherwise uses largely surface-oriented graphical aids to reconstruct coherence or argumentative thematic connections. In Figures 2.3.4-9 and 10, the technique of "persistent cards" is used on the one hand, and the technique of "persistent gestures" on the other. In the first case, the thematic continuity in the sequence of a "guided tour" should be indicated by identical (or largely identical) screen design. Thus, the structure of Fig. 5 (Fig. 2.3.4-9), where the general definition of "dangerous felony" is given, is preserved in Fig. 6 (2.3.4-10), since in both the main theme remains constant and only one concrete example is given. "Persistent gestures" are used as stylistic devices and structuring aids in these two sections as well. The positive and negative arguments are separated by the cards marked with "grey arc". In Fig. 6 (2.3.4-10) it becomes clear that the majority of the arguments are concentrated on the left side.

From a text-linguistic point of view, one might be tempted to consider the means used as tricks and inadmissible surrogates. They are in fact largely formal and surface-oriented, i.e., they do not provide any interpretation of the contents, and, moreover, they have to be created intellectually by the authors of the hypertext base. Thus, they are largely predetermined. However, as we have seen, it is extremely difficult to keep coherence and context stable in hypertext in general, since access to hypertext is systematically interactive and it is ultimately up to the user to decide which (even of the offered) direction(s) to take or how many windows or maps in NoteCards to keep open in parallel. The attempt to make structures and decision situations transparent by means of a multitude of meta-information cannot yet be assessed in terms of its acceptance or its confirmation, since there is still too little "reading" experience with these means. It is therefore not yet possible to make any reliable statements about the extent to which users are willing and able to follow paths or "guided tours" that require a high degree of control and guidance aids. However, it is already clear that this approach used by NoteCards requires careful and elaborate "screen management" based on ergonomic design techniques.

[…]

[…] NoteCards also continues to work on the "guided tours". Marshall/Irish (1989) summarize the following points, which can improve the performance so far: - annotated graphical overviews; - tour stops that explain layout conventions; - integration of explanatory text with other types of metainformation; - context-sensitive referencing; - persistent gestures and maps; - tools to support activities from other disciplines; - examples of successful presentation strategies.

[…]

If, according to the principles of this text theory, argumentation schemes can be offered for the design of navigation paths in hypertext prototypes, then a future middle way between the completely free associative "browsing" and the rather restrictive specifications of "guided tours" (see section 2.3) can be taken. Schemes of the kind indicated serve as a general orientation framework for the reader during navigation, whereas in any actual navigation the schemas are concretized by the information of the actual informational units. In the following, we compile which rhetorical-illocutionary schemes have been provided for use in hypertext so far in the described domain: […]

~

KUHLEN, Rainer, 1991. Hypertext: ein nicht-lineares Medium zwischen Buch und Wissensbank. Berlin: Springer. Edition SEL-Stiftung. ISBN 978-3-540-53566-9.

Marshall, C.C.; Irish, P.M. (1989): Guided tours an.d on-line presentations: How authors make existing hypertext intelligible for readers; in: ACM-Hypertext (1989), 15-26.