In 2001, seventeen software developers met together at a ski resort. They all sensed that the traditional way software was being developed, using a rigid production process, wasn’t working. Each of them had been experimenting with new ‘lightweight’ methods that allowed teams to build more powerful solutions exponentially faster. They found common ground and wrote the Agile Manifesto, launching a movement that would transform not only the software industry but also how businesses are managed. Today, over 70% of companies have adopted agile practices to innovate faster, recognizing that competitive advantage in the new creative economy is based on adaptability and the rate of innovation.

At the core of agile are fast, iterative learning cycles where teams are continually challenged to Walk into the Unknown in which failure – better thought of as ‘surprise’ – is expected. _Each surprise illuminates incorrect assumptions in their cognitive model, allowing the deeper nature of the problem, and its potential solution, to more quickly emerge._

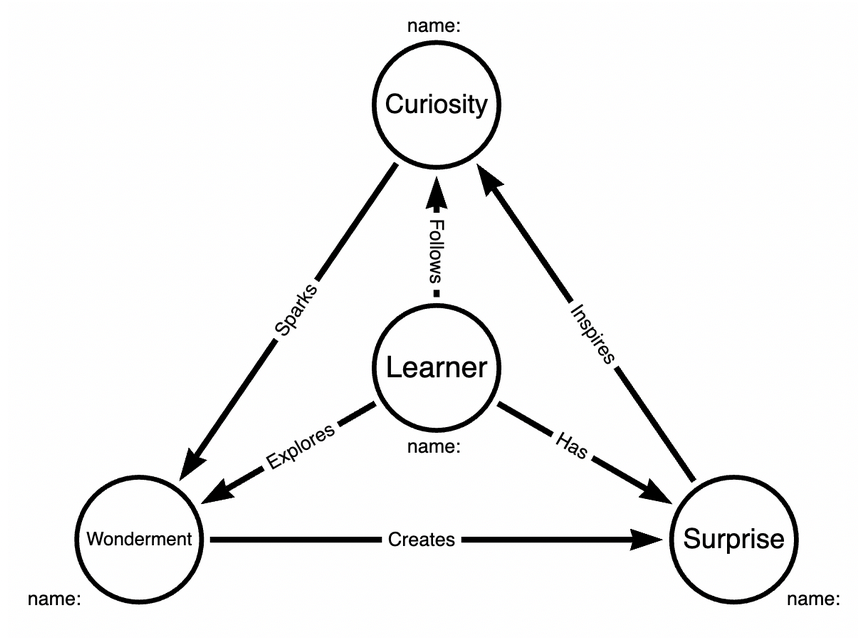

Using new paradigms of learning, based on the pioneering work of neuroscientist Karl Friston, the power of this learning mindset can be distilled to a simple model. His theory of Active Inference allows us to not only understand the transformative impact of agile within companies but also the fundamental nature of ‘active learning’ theories in education traced back to Piaget, Vygotsky, and others.

Learning Schema

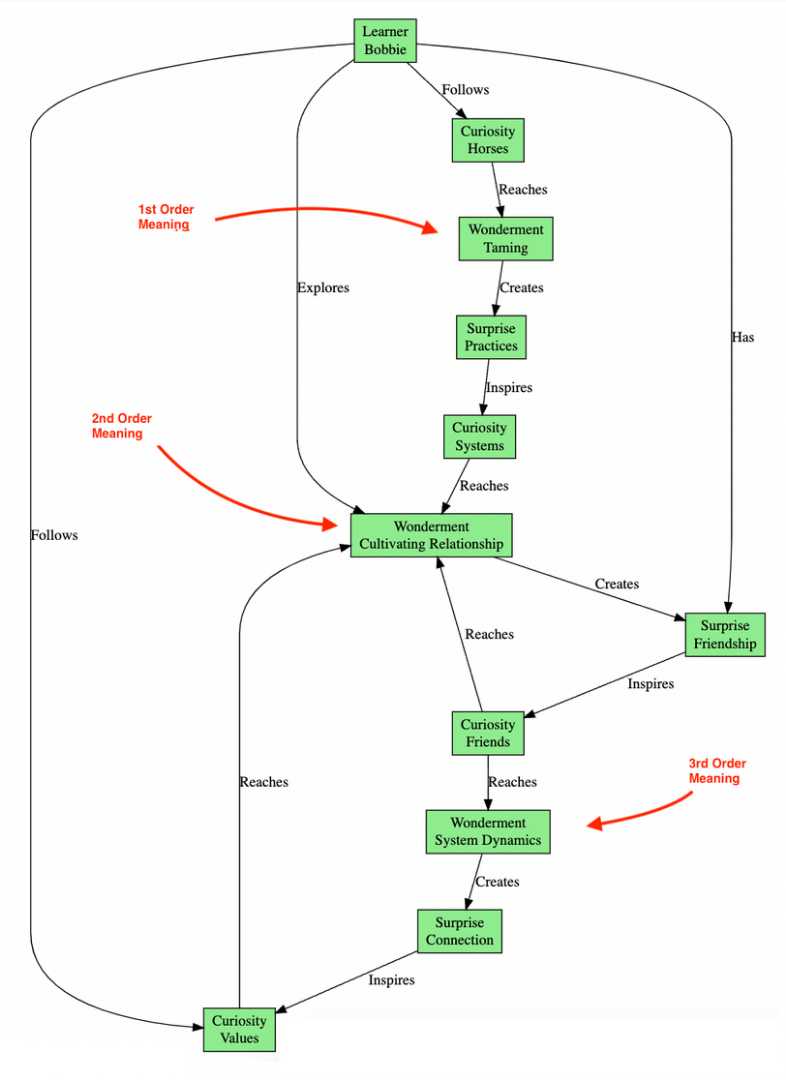

As teachers begin to use the agile-based DiG learning framework, students are challenged to go beyond ‘first level’ thinking as they turn the lens of their focus inward to themselves when they explore new knowledge.

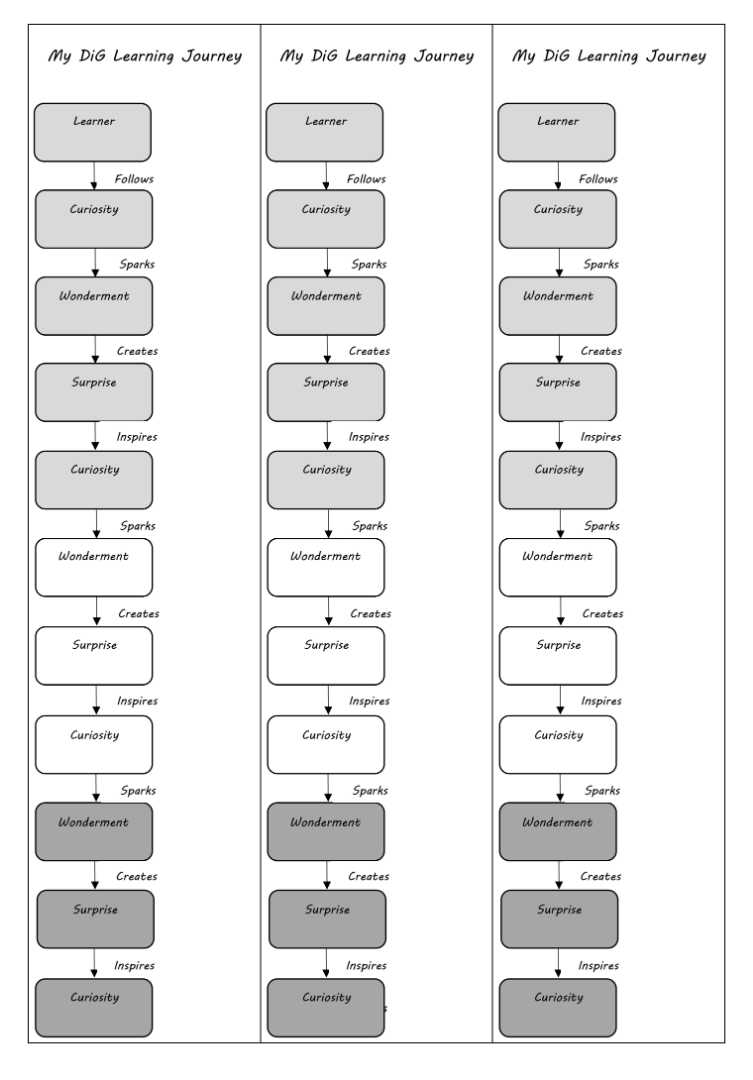

Journey Mapping

By integrating the practice of interoception in their learning, learners begin to trust their intuition to dig deeper into their own lived experiences as they seek personal meaning. Here we sense the potential when the feelings from episodic memory allow the emergence of meaningful ‘aha moments’ that become stored as concepts in their long-term semantic memory.

It’s through stories that the learning is shared with others. Critical to this process is the making of a creative artifact as a vessel for these stories. The kinetic act of making the artifact helps the learner to understand the meaning of their story more deeply, allowing the telling of their story to become more powerful and building their creative confidence.

By graphing their stories as they followed their intuition into deeper depths of feeling, they are able to illuminate what we call ‘third-order meaning’ – evidence of Deep Learning – that feels magical for themselves and others as it could not have been anticipated when the learner originally embarked on their learning journey.

Story of Meaning

DOT FROM preview-next-diagram