While human life is certainly a manifestation of biology, social relations (culture) are the origin of what distinguishes humans from other animals (Vygotsky, 1997b).

Therefore, qualitative changes in human Behavior are not merely biological, though necessarily enabled by them. Instead, when a Person—in Vygotsky’s discussion, virtually always Children generally accompanied by teachers or more capable peers—engages in joint labor (behavior) with another person, then that relation may later show up as the individual labor (behavior). >> behavior child

Thus, when Vygotsky writes about the growth of logical memory, he points out that there are not only quantitative changes, but also qualitative changes of the function of remembering in terms of “its composition, structure, and method of action” (Vygotsky, 1998: 98). The joint labor provides for a zone of proximal development, where qualitatively new forms of acting arise out of participation in some task. Participation in the relation and individual contributions to joint actions necessarily are at the person’s current developmental levels; but that participation provides for a changeover to a qualitatively new level. Importantly, whereas changes prior to the developmental change were incremental, development itself is characterized as a qualitative change, a transition between qualitatively different forms of behavior. Thus, following the changeover, subsequent incremental change will take a very different form from that which had taken place prior to the qualitative leap. It is therefore important to differentiate between cumulative, quantitative change within a form of behavior and transformative and revolutionary change that leads from a first to a second, qualitatively different form of behavior. >> changeover zone

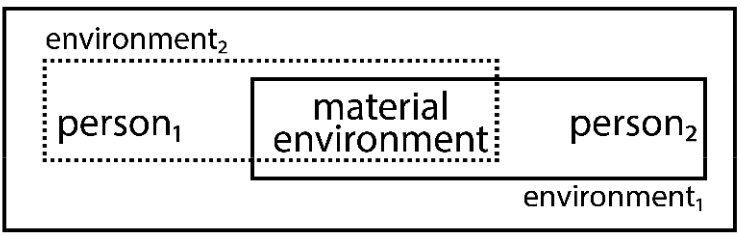

Figure 4. The system under consideration in developmental studies; no part can be considered independent of any other part.

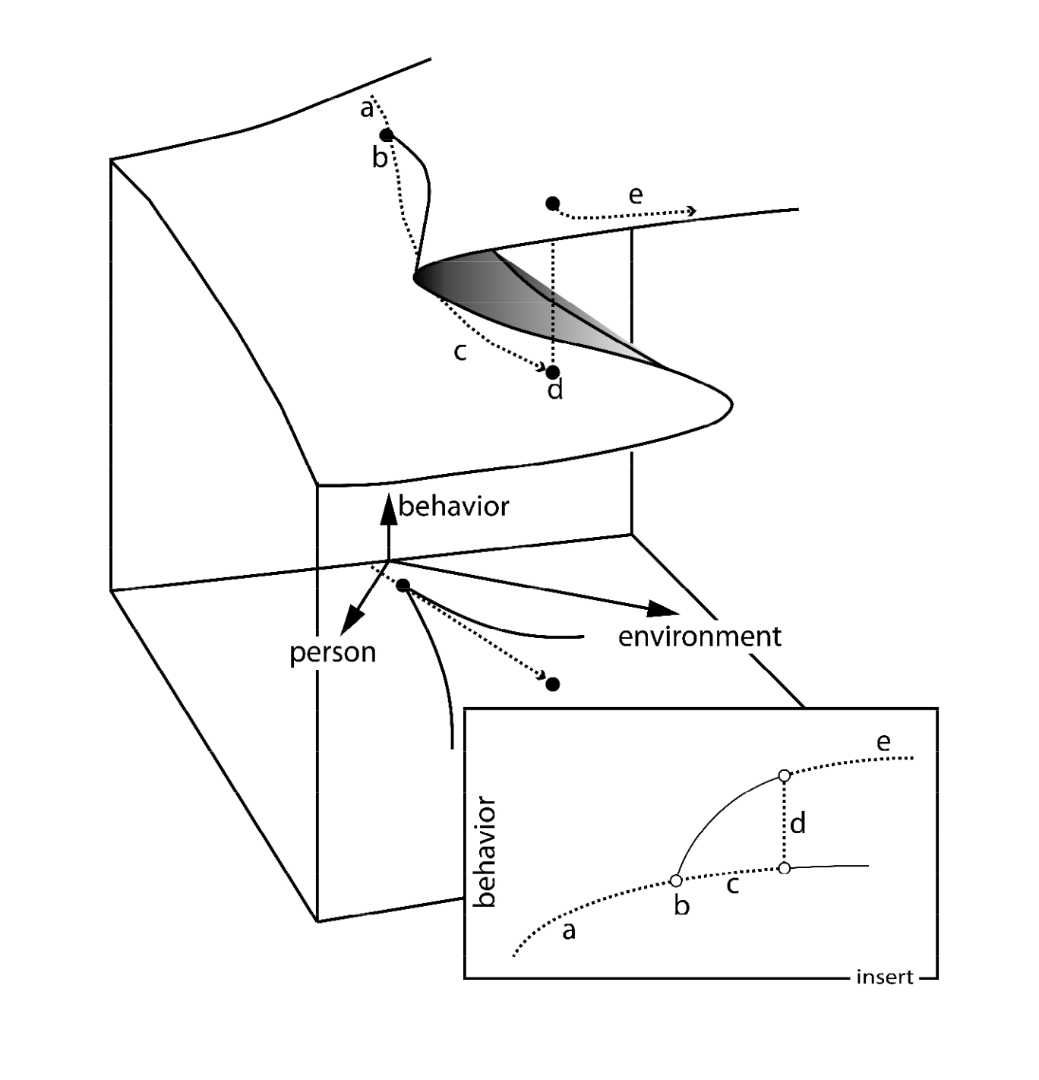

Once we conceive our system in this way, it is apparent that the very presence of the adult may, but does not have to, create a situation equivalent to the Fold (Figure 2). […]

Figure 2. Depiction of the Cusp Catastrophe exemplified for a {person | environment} system. The insert follows the system’s Path highlighting the genesis of a new system function (behavior) at the first catastrophe “b” and a sudden transition at the second catastrophe “d,” where the heretofore minor behavior becomes the dominant one, whereas the previously dominant one comes to subsist as a possibility in the background.

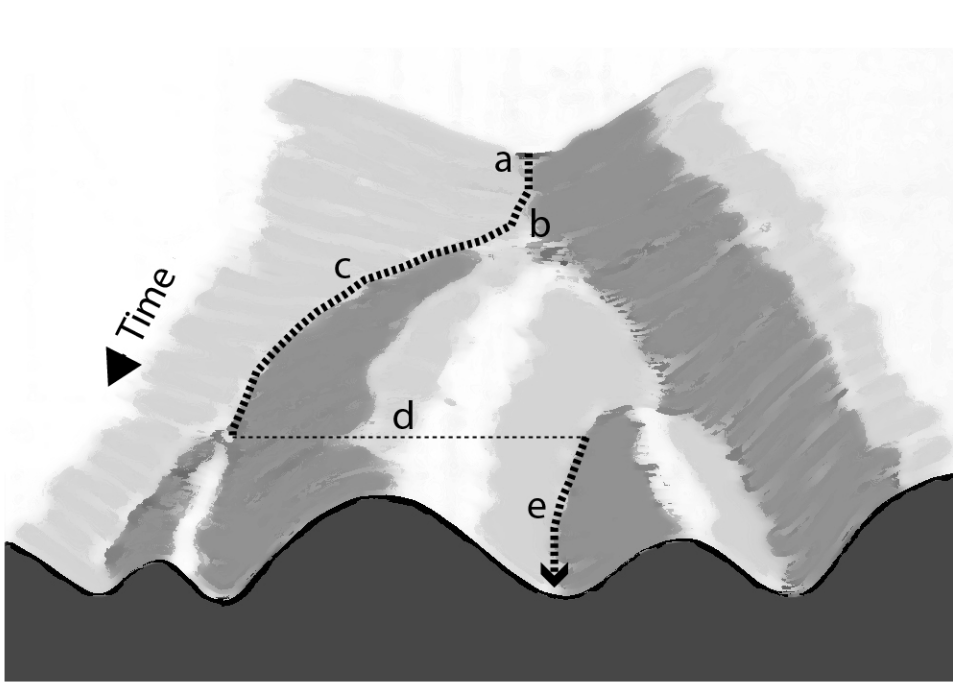

This catastrophe theoretic model for the emergence of new forms—i.e., Morphogenesis—has been used to provide an account for an alternative model of Evolution. In it, the phenotype of a particular organism is thought in terms of a ball rolling along the valley bottom of a complex (epigenetic) landscape (Figure 3). The system here is denoted as {genotype | (epigenetic) environment}. >> morphogenesis evolution

Figure 3. Trajectory of a {genotype | (genetic) environment} system in its epigenetic landscape. Variations anywhere in the system can flip it (horizontally) from one into another valley and, therefore, from one growth trajectory into another with very different phenotypic expression.

Whereas there are two stable states within the fold for the first case of a system (Figure 2, branches c and e), the second example (Figure 3) has four valleys at the very front of the depiction. We see that these valleys have formed as part of the evolution of the system (from the back to the front). The system tends to be relatively stable at the valley floor. However, variations at either pole of the {genotype | (genetic) environment} system can push it into another valley corresponding to the qualitative change in Figure 2, d. The particular model, known as the Cusp Catastrophe, also is useful for classifying the kinds of empirical observations contained in the two vignettes. >> cusp catastrophe

In the first case, we observe a student (Aslam) who, in the course of the relation with the investigator, changes the dominant form of responding to balance beam tasks from an additive strategy to a multiplicative (ratio and proportion) strategy. Although a certain level of biological development is the condition for such a change, the behavior is a typically human one and, therefore, understandable as a qualitative change in behavioral terms. For the particular case, we do not have available historical information and, therefore, do not know the extent to which Aslam already described phenomena in terms of doubling, tripling, and so on in other situations of his life. However, it is certain that he has had experiences in mathematics that deal with the relations between numbers. We may therefore assume that he already is familiar with such (mathematical) practices but, in the early part of the clinical interview, did not employ them to deal with the balance beam task. There are two aspects that have not been addressed or theoretically captured in the Piagetian literature: (a) the change in the task that the interviewer sets up and (b) the existence of a social relation, existing in and produced by the joint labor. That is, without requiring any biological maturation, we observe a relatively quick transition (occurring over the course of a few verbal exchanges) to the use of a new way of dealing with balance beam tasks. Over time, this new form also includes more complex problems that Aslam does not initially solve, initially falling back on the additive approach before seeking a way to expand ratio reasoning.

In the second case, Leandro, we observe a rather sudden creation of a new form of consciousness concerning teaching and the changeover to the new way of understanding his reality of teaching. This changeover then provided a way of preparing lessons in a new way, so that, over a period of incremental changes, Leandro increasingly made his planning and implementation of lessons consistent with the new form of consciousness. In this case, the time between the emergence of a new form of consciousness and its becoming the dominant form was relative brief, occurring over the course of one (six-hour) long discussion that lasted until late into the night. If the duration of that meeting were plotted against Leandro’s entire teaching experience, it would appear to have occurred instantaneously, even though it had its own temporality. As before, there were personal and environmental characteristics involved. Both the journal article and the discussion with his fellow inquirers are environmental characteristics that are associated with the emergence and amplification of dissatisfaction Leandro experienced with his then-current form of teaching. It was after a second reading of the “Poop” article, apparently occurring during that long evening, that a feeling emerged that he had received a double slap in the face, and the simultaneously articulated rejection of his earlier teaching methods.

Catastrophe Theory only provides a way of classifying morphogenetic processes and events. It does not provide (social) psychologists, educators, or learning scientists with principles of method that direct researchers to search for and describe necessary and sufficient evidence for the transformation of quantity into quality. Whereas the catastrophe-theoretic description (Figure 2) makes apparent what is required—i.e., evidence for the five distinct parts in the growth trajectory of behavior—it was precisely K. Holzkamp who outlined in the Grundlegung a set of necessary and sufficient forms of evidence that would accomplish such a task.

~

ROTH, Wolff-Michael, 2019. How to generate evidence for the emergence of new psychological forms: Grundlegung der Psychologie and its contribution to method. Kritische Psychologie. 2019. Vol. 16, p. 719–740.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, vol. 1: Problems of general psychology. New York: Springer.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1989). Concrete human psychology. Soviet Psychology, 27(2), 53–77.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997a). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, vol. 3: Problems of the theory and history of psychology. New York: Springer.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997b). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, vol. 4: The history of the development of higher mental functions. New York: Springer.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1998). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky vol. 5: Child psychology (R. W. Rieber, Ed.). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Lew Semjonowitsch Wygotski de.wikipedia ![]() , en.wikipedia

, en.wikipedia ![]()