TDD was invented in Smalltalk via the introduction of the SUnit test library.

When you code, alternate these activities:

www.zeroplayer.com

add a test, get it to fail, and write code to pass the test (Do Simple Things, Code Unit Test First)

remove duplication (Once And Only Once, Dont Repeat Yourself, Three Strikes And You Automate)

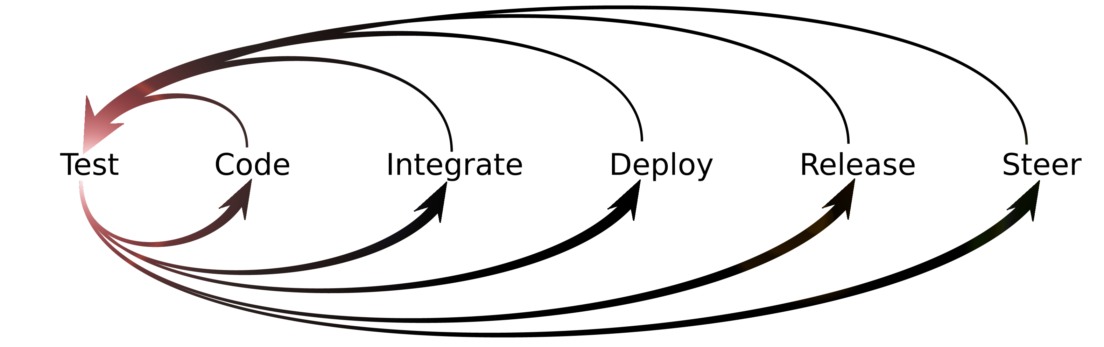

This inner loop pumps the outer loops of Extreme Programming - Continuous Integration, Daily Deployment, Frequent Releases, and Steering Software Projects. (Hence the graphic.) Tests help us keep promises regarding the quality, cost, and existence of previously installed features.

Using this system, all my code is highly decoupled (meaning easy to re-use) because it all already has two users - its clients, and its test rigs. Classes typically resist the transition from one user to two, then the rest are easy. I make reuse easy as a side-effect of coding very fast.

Then, the "remove duplication" phase forces one to examine code for latent abstractions that one could express via virtual methods and other techniques that naturally make code more extendable. This is the "reuse" that the OO hype of the 1980s screamed about.

Think about what you want to do.

Think about how to test it.

Write a small test. Think about the desired API.

Write just enough code to fail the test.

Run and watch the test fail. (The test-runner, if you're using something like JUnit, shows the "Red Bar"). Now you know that your test is going to be executed.

Write just enough code to pass the test (and pass all your previous tests).

Run and watch all of the tests pass. (The test-runner, if you're using JUnit, etc., shows the "Green Bar"). If it doesn't pass, you did something wrong, fix it now since it's got to be something you just wrote.

If you have any duplicate logic, or inexpressive code, refactor to remove duplication and increase expressiveness -- this includes reducing coupling and increasing cohesion.

Run the tests again, you should still have the Green Bar. If you get the Red Bar, then you made a mistake in your refactoring. Fix it now and re-run.

Repeat the steps above until you can't find any more tests that drive writing new code.

Please note that first item is by far the most difficult, followed by the second item. But if you can't do those, you probably shouldn't start writing any code. The rest of the list is really pretty easy, but the first two are critical.

Uh, item 1 is what your Onsite Customer keeps screaming about, and item 2 is just item 1 stated inside-out. They are all easy, especially in this order.

There is a big step between hearing the words of an Onsite Customer and understanding the meaning. Translating a business statement into technical language can be a difficult job and one should respect that difficulty. Item 2 recognizes that testing the code often requires exposing some things not necessarily required by the end user. There is a step to go beyond what the user needs to what the test will need.

An example of TDD in action in a simple challenge - to write a programme that produces the correct answers to the game "Fizz Buzz": www.youtube.com ![]()

I use code to find patterns that I am interested in. I can imagine many possible solutions to programming problems but some are a lot better than others. Rather than use my brain to model the computer in high resolution, I use the computer itself to do the modeling and all I need is to start coding somewhere, make incremental changes and follow what turns out to be interesting. Most of this kind of code is thrown away so why would I want to make it bullet proof up front? If I was creating a UI for a piece of code, I would create many versions until I zeroed in on the one I like. Test first is great if you know exactly the best way to program an explicitly defined program but I rarely get that kind of explicit definition and even if I did, how would I know that technique "best fits" that problem? I would know that if I had coded something very like it before but if I had, then I would just take the code I wrote before and make modifications to it. Creating tests that proves the code works is very hard, except in the simple cases and those probably don't need a test in any case. Tests should be created for code that is a "keeper" which, in my case, is only a small fraction of the code I write.

How do you write a test for something that is constantly changing and you don't know what it's shape or structure will look like?

-- David Clarkd

Systems created using Code Unit Test First, Relentless Testing & Acceptance Tests might just be better designed than traditional systems. But they all certainly would support Code Unit Test First while using them better than our current set of systems.

But because so danged many of them were not, we are a little blind to what we could have available on the shelf.

A list of ways that test-first programming can affect design:

Re-use is good. Test first code is born with two clients, not one. This makes adding a third client twice as easy.

Refactoring test-first code results in equally tested code, permitting more aggressive refactorings (Refactor Mercilessly). Cruft is not allowed, and code is generally in better shape to accept more refactorings.

When paying attention during all of the little steps, you may discover patterns in your code.

Test code is easy to write. It's usually a couple calls to the server object, then a list of assertions. Writing the easy code first makes writing the hard code easy.

Design Patterns may be incremented in, not added all of a bunch up front.

Test-first code is written Interface first. You think of the simplest interface that can show function.

Code tends to be less coupled. Effective unit tests only test one thing. To do this you have to move the irrelevant portions out of the way (e.g., Mock Objects). This forces out what might be a poor design choice.

Unit Tests stand as canonical & tested documentation for objects' usage. Developers read them, and do what they do in production code to the same objects. This keeps projects annealed and on track.

When the developer has to write tests for what he is going to do, he is far less likely to add extraneous capabilities. This really puts a damper on developer driven scope creep.

Test First Design forces you to really think about what you are going to do. It gets you away from "It seemed like a good idea at the time" programming.

- This sure isn't a page for irresponsible people. Is any programming activity for irresponsible people? See Code And Fix, Water Fall.

- Nope. the problem is: They don't know! [Unskilled And Unaware Of It]

I have been working my way through Kent's TDD book for a while now, and applying the principles quite rigorously. I am a real dullard sometimes, because it takes me a horribly long time to understand even simple stuff. I had probably been applying TDD for more than a week before I realized why it works so well (at least for me). There are three parts to this:

The tests (obviously) help find bugs in the application code, and the micro-steps taken with TDD mean that any "bugs" are in the very code I have just been writing and hence which still has a relevant mental model in my small brain

By doing the absolutely simplest thing in the application code in order to get each test to run, I often have small Aha Moments, where I see that I am writing such overly concrete code (i.e. just enough to get the tests to work) that the tests (even though they run) cannot possibly be adequate to cover the "real" requirements. So to justify writing more abstract application code, I need to add more test cases that demand that abstraction, and this forces me to explore the requirement further. Therefore, the application code actually helps me debug the tests. That is, since the tests are the specification, feedback from the application code helps me debug the specification.

As I have these "aha!" moments (mentioned in 2 above) I follow Kent's practice of adding them to the To Do List. It took my stupid head quite some time to realize that the TODO list is actually a list of Micro-Stories, which I constantly prioritize (since I am the customer at this level). Following Alistair Cockburn's insight that Stories are promises to have a conversation with the customer, I see, then, that the Micro-Stories in the TODO list are a promise to have a conversation with myself (and, here is the weird bit) to have a conversation with the code (since it gives me feedback - it tells me things - and TDD tunes me in to listening to the code).

Test Driven Development (TDD) by Kent Beck

images.amazon.com

[ISBN: 0321146530] A Book,

Mailing list: groups.yahoo.com ![]() .

.

Test Driven Development (TDD) by David Astels

[ISBN: 0131016490] another book

John Rusk worries that one danger of Test Driven Development is that developers may not take that step that you take. I.e. developers may stay with overly concrete code that satisfies the tests but not the "real" requirements.

To look at it another way, I have always felt that it was dangerous to approach design with (only) particular test cases in mind, since its usually necessary to think about boundary cases, and other unusual cases.

How does XP address that danger? By encouraging developers to write sufficiently comprehensive tests? Or by relying on developers to take that step which you mention, which is saying, "OK, this actually passes my tests, but its not really adequate for the real world because....".

XP addresses that danger with Pair Programming. When obvious boundary cases are overlooked by the programmer driving the keyboard, the programmer acting as navigator points out the oversight. This is an excellent example of a case where a single practice is, by itself, insufficient to reasonably guarantee success but, in combination with a complementary practice, provides excellent results.

Test First is a cool way to program source code. XP extends Test First to all scales of the project. One tests the entire project by frequently releasing it and collecting feedback.

Q: What "real" requirements can you not test?

Those requirements which are not stated.

Requirements which require highly specialized, unaffordable, or non-existent support hardware to test. E.g., with hardware such as the Intellasys SEAforth chips, it's possible to generate pulses on an I/O pin as narrow as 6ns under software control. To see these pulses, you need an oscilloscope with a bandwidth no less than 166MHz, and to make sure their waveform is accurate, you need a bandwidth no less than 500MHz, with 1GHz strongly preferred. However, at 1GHz bandwidths, you're looking at incredibly expensive sampling oscilloscopes. Thus, if you cannot afford this kind of hardware, you pretty much have to take it on faith things are OK. Then, you need some means of feeding this waveform data back to the test framework PC (which may or may not be the PC running the actual test), which adds to the cost.

TDD cannot automatically fix algorithms; neither can any other technique. Where rigorous testing helps is ensuring that the details of your algorithm remain the same even if you refactor or add features. A test case can easily check _too_ much, and fail even if the production code would have worked. For example, suppose one step of an algorithm returns an array. A test could fail if that array is not sorted, even if the algorithm does not require the array, at that juncture, to be sorted.

This is a good thing; it makes you stop, revert your change, and try again.

Note: here is the link to the pdf file on the yahoo groups area:

I found this unexpectedly awkward to locate by searching, so I thought I'd drop the link in here. -- David Plumpton

I've sometimes been an advocate of test driven development, but my enthusiasm has dropped after I've noticed that Code Unit Test First goes heavily against prototyping. I prefer a style of coding where the division of responsibility between units and the interfaces live a lot in the beginning of the development cycle, and writing a test for those before the actual code is written will seriously hinder the speed of development and almost certainly end testing the wrong thing.

Agreed. Please see my blog entry about adapting TDD for mere mortals at agileskills2.org ![]() -- Kent Tong

-- Kent Tong

: Assuming you're not shipping the prototype, there's nothing particularly in conflict. The prototype is in itself a sort of design test. The trouble with prototypes is that they have this habit of becoming the product...

[RE: prototypes becoming "the" product. Arrg.. I agree. No reason for it to happen. TDD makes rewriting slops as clean code absurdly easy]

Design is a lot more difficult than implementing a design. But Unit Tests explicitly require one to define the design before making it work.

There are other problems, too. Like OO methodology, the difficulties which test driven development helps with are sometimes caused by itself. Every extra line of code adds to the complexity of the program, and tests slow down serious refactoring. This is most apparent in hard-to-test things like GUI's, databases and web applications, which sometimes get restructured to allow for testing and get complicated a lot. -- Panu Kalliokoski

Code Unit Test First goes heavily against prototyping? Strange, I haven't found that to be true, myself. Closer to the opposite, in fact - I start with a very thin shell of a Proto Type, and as I make progress it fills in with real features. I wonder how what you actually do differs from what I actually do.

Strongly agree. A big side benefit of Code Unit Test First that doesn't get enough attention is how it rearranges your thinking. Instead of thinking "oh I'll need these accessors on these classes, etc" you think in terms of use cases. And you end up with *exactly* what you need, nothing more and nothing less.

I find I have a huge increase in speed in all areas of development when I Code Unit Test First. I honestly believe that anyone who doesn't experience this is either busy knocking down Straw Mans, isn't doing it right, or hasn't really given it a chance.

TDDing GUIs is quite frustrating. It may be a lot easier if there were a GUI toolkit available that has been TDDed itself, from the ground up. Anyone interested in such a TDDedGuiFramework project?

You mean like Ruby On Rails? -- Phl Ip

:-) No, I mean a toolkit for standalone clients (or maybe a hybrid one, people have been experimenting with this already). Something like SWT, but a lot more intuitive :-)

Note that some TDDers abuse Mock Objects. Dynamic mock systems like classmock.sf.net ![]() can make this too easy. A TDD design should be sufficiently decoupled that its native object work fine as stubs and test resources. They help to test other objects without runaway dependencies. One should mock the few remaining things which are too hard to adapt to testing, such as random numbers or filesystem errors.

can make this too easy. A TDD design should be sufficiently decoupled that its native object work fine as stubs and test resources. They help to test other objects without runaway dependencies. One should mock the few remaining things which are too hard to adapt to testing, such as random numbers or filesystem errors.

Some of us disagree with that view, see www.mockobjects.com ![]() for an alternative.

for an alternative.

I'd like to revisit a comment that John Rusk made above:

It seems to me that one danger of Test Driven Development is that developers may _not_ take that step that you take. I.e. developers may stay with overly concrete code that satisfies the tests but not the "real" requirements.

The principles of TDD can be applied quite well to analysis and design, also. There's a tutorial on Test-driven Analysis & Design at www.parlezuml.com ![]() which neatly introduces the ideas.

which neatly introduces the ideas.

-- Dave Chan

What about extended the principles of TDD beyond testing, analysis, and design. How about using the principles also on user documentation? This idea is described in Purpose Driven Development (PDD) at jacekratzinger.blogspot.com ![]()

"Roman Numerals" is often held up as a good sample project to learn TDD. I know TDD but I'm bad at math, so I tried the project, and put its results here:

-- Phl Ip

Up to date info on tools and practices at testdriven.com ![]()

-- David Vydra

I found GNU/Unix command line option parsing to be a good TDD exercise as well. My results here:

home.comcast.net ![]() (3.5Mb download; 4.7Mb unpacked)

(3.5Mb download; 4.7Mb unpacked)

-- Paul Holser

Organic Testing of the Tgp Methodology is one way to practice Test Driven Development. Organic Testing is an Automated Tests methodology that share resemblance to both Unit Test and Integration Test. Like Unit Test, they are run by the developers whenever they want (before check-in). Unlike Unit Test, only the framework for the test is provided by the programmers, while the actual data of the test is given by Business Professionals. In Organic testing like Integration Tests, in each run the whole software (or a whole module) is activated. -- Ori Inbar

Another reference: article "Improving Application Quality Using Test-Driven Development" from Methods & Tools

But what about Secure Design? Security As An Afterthought is a bad idea and it seems that test-driven development (and a number of other agile processes, though perhaps not all) has a bad habit of ignoring security except as test cases, which isn't always the best way to approach the problem.

-- Kyle Maxwell

Hmmmm. Seems to me that TDD deals with security (as well as things like performance) just like any other functional requirement. You have a story (or task) explicitly stating what functionality is needed (e.g., user needs 2 passwords to login, which are stored in an LDAP server; or algorithm needs to perform 5000 calculations per second). You then write tests that will verify functionality. And then you write the functionality itself.

And unlike traditional development, you now have regression tests to make sure that this functionality never gets broken. (i.e., if, due to subsequent coding, the security code gets broken, or the algorithm performance drops off, you'll have a broken test to alert you of that.)

One of the reasons that security is hard is that security is not just a piece of functionality. Okay, there are things like passwords which are security features, but the rest of the code also has to not have security holes, which are Negative Requirements; ie, code must not do X.

This is obvious in the case of 'must not overflow buffer', which TDD does address, but is less obvious in things like 'component X should not be able to affect component Y'. How do you test that? (I probably read this in 'Security Engineering', by Ross Anderson, which is now free on the web).

-- Alex Burr

In the case of "Component A must not affect Component B", how would you evaluate this without test-driven development? If you can't formally define this requirement, then TDD is no better or worse than hoping for the best. (One answer in this case may be rule-based formal validation of the system, which is easy enough to plug into a TDD framework.) -- Jevon Wright

Some interesting info on test driven development from E. Dijkstra:

(above is from www.cs.utexas.edu ![]() )

)

Bit Torrent founder (Bram) uses test driven development, and thinks Formal methods suck:

IEEE Software will publish a special issue on Test-Driven Development in July 2007. For more information, see Ieee Software Special Issue On Test Driven Development

Found this useful illustration of TDD in .NET (Flash screen cast)

www.parlezuml.com ![]()

I can't help to mention the awesomeness of Doc Test in Python. Not only do you get TDD, but you get code documentation for free, as it integrates Doc Strings into every Module, Class, and Method. I'd like to see TDD really integrated tightly into programming environments. Doc Strings are accessed via a built-in help() function and encourage a friendly development community. Doc Test goes further, encouraging smart design of tests within the Doc Strings themselves in ways that simultaneously teach the User what your method and class is supposed to do. Ideally, Interpreted environments should integrate a test() built-in. Then, Doc Test could be removed and built into the interpreter environment with it`s companion function "help()". This would allow the "add a test, get it to fail, and write code to pass" cycle to attain a most friendly goal of Literate Programming. -- Mark Janssen

BDD (Behavior Driven Development) is a form of TDD (Test Driven Development) where the tests are specified through definition of desired Behaviors, as opposed to writing tests in code (the same code language used for the product). The BDD camp says that you use natural language to describe desired behaviour, and employ testing tools which translate the natural language behaviour specification into tests which validate the product code. This approach recognizes and attempts to address a couple of challenges with testing which I elaborate upon below.

See 'Cucumber' (cukes.info ![]() ) as one example of a BDD test toolkit.

) as one example of a BDD test toolkit.

One strategy with BDD is that you employ test (SDT) developers with much different skills than your product (SDE) developers. You can thereby segregate SDT and SDE developers by skills. Another strategy is that your developers use different tools for product development from test development. This suggests that you use people with different skills (less product intensive skills, btw), to write tests (or the same folks using different skills). But when you choose TDD or BDD as a methodology practice, you need to consider (answer) the questions exposed below.

Building test code to automate the testing of your product code produces a regression problem. You want to avoid placing 'faith' in the production code, and ensure that the code has been tested (verified), but now you have moved your 'faith' into the test code.

This regression problem is a challenge with testing, where you must provide tests which cover the requirements and features of your product, so you have moved (regressed) the problem of (potential) defects in the development into a problem with (potential) defects in the test code. You have now written more code (probably in the same language), but possibly replicated or moved the defect into test code. You are still placing faith, but now in your test code, rather than in your production code.

One strategy is to use SDT's to develop tests, and SDE's to develop products. This can help catch misunderstandings in requirements (win), but only increases the amount of code written, and thus the potential number of defects, adding personnel to develop these tests, and thus adding costs. And you now have a recruiting and motivation problem. You must staff SDE's to build products and SDT's to build tests.

However, we can consider that by using different personnel, defects are statistically less likely to align between product code and test code, because we assume that the SDE's and SDT's are independent. We assume a stochastically independent defect generation (SDE's and SDT's are different people). Thus we expect them to generate defects in different places.

But are these activities stochastically independent? We are relying upon this independence. But agile asks that one agile team combine developers writing production code and developers writing test code. So the same (hard) problems are viewed by the same team, and the same conceptual issues are tackled in code by the same pool of developers. Using different developers to write product and test code gains little practical independence, as developers (SDE or SDT) have essentially the same training and experience.

Consider the strategy that you require different training and experience from SDE and SDT. This regains some missing independence. But unless all developers (SDE and SDT) have essentially the same training, capabilities, and skills, they cannot perform interchangeably on an agile team. And developers undertake extensive training. And now you must separate developers by skill and role. Now you face the choice whether to use more skilled developers to write the product, or to write the tests? Using less skilled developers to write the product impairs your product. Using less skilled developers to write your tests means that you impair your tests. This reduces to a Faustian choice, do you effectively subvert your testing and quality process, or do you sacrifice your product development?

Revisit the recruiting and motivation problem. Suppose you decide to staff SDT's to build tests and SDE's to build products. You have introduced stratification and competition into your development team. Are you going to get equally qualified candidates for both SDE and SDT? Even with the different requirements? Assume that most developers want to advance their careers, and gain recognition and rewards, and become the best developers they can become.

Which path will the best and the brightest want to pursue? Consider that Google hires less than 1% of applicants (lots of people want to work there, so they must want to pursue the 'best' career path). Joel Spolsky (co-founder, Fog Creek Software) writes a blog on software development, (www.joelonsoftware.com ![]() ), says that you should hire people who are "Smart, and Get Things Done".

), says that you should hire people who are "Smart, and Get Things Done".

Can you effectively use the same people writing both product code and test code? And gain the stochastic independence testing needs? Can you use people with different training and skills, and have them independently build tests? And not sacrifice product development on the altar of quality?

The BDD camp says that you use natural language to describe desired behaviour, which would employ developers with much different skills, and thereby segregate developers by skills. This suggests that you use people with different skills (less product intensive skills, btw), to write tests. This has been exposed as a suspect strategy, but assuming you choose TDD or BDD as a methodology practice, anyway. How do you achieve the best results?

TDD in general and Behavior Driven Development in particular are firmly grounded in Hoare Triple. I find a useful parallel between a written Use Case document and BDD Feature / Story Narrative.

See Test First User Interfaces Calvin And Hobbes Discuss Tdd Test Driven Analysis And Design Test Driven Developmenta Practical Guide Test Driven Development Challenges Test Driven Design Phase Shift, Power Of Tdd, Ieee Software Special Issue On Test Driven Development, Behavior Driven Development, Test Food Pyramid

See original on c2.com ![]()